Destination Stewardship Report – Winter 2021 (Volume 1, Issue 3)

This post is from the Destination Stewardship Report (Winter 2021, Volume 1, Issue 3), an e-quarterly publication that provides practical information and insights useful to anyone whose work or interests involve improving destination stewardship in a post-pandemic world.

For 20 years, ecotourists have been eager to tour a biodiverse volcanic island off the coast of Taiwan. But what happens when both locals and tourists complain about the stringent conservation limits on visitation set by government and academics? Monique Chen explains how stakeholders have harmonized ecological carrying capacity and local economics.

A Taiwanese Island Boosts Tourist Capacity – Sustainably

By Monique Chen

Turtle Island in profile. Photo: Roi Ariel

Taiwan’s Turtle Island, an active volcano known for its turtle-like shape, claims a rare lily, an endangered flying fox, a dazzling coral reef, a thriving ecosystem, and a “Milk Sea.” Its proximity to Taipei makes it a tourism magnet – and a management challenge.

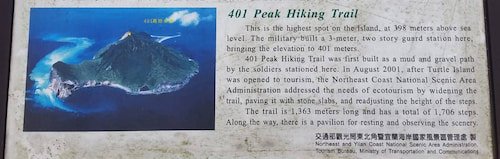

The island lies 10 km east off of Taiwan’s Northeast and Yilan Coast National Scenic Area (NEYC), named as one of the Top 100 Sustainable Destinations from 2016 to 2020. Known as Guishan Island in Mandarin, it has a surface of area of 2.85 km2 and a high point of 398 meters above sea level with an unused military outpost on top of the hill. The island’s location off the northeast coast puts its ferries within an hour’s drive of Taipei, and then a mere 20-minute boat ride to the island.

Dated back to the Qing Dynasty (around the 18th century), Turtle Island had a population of 700 villagers at its peak. The whole village was relocated to the main island in 1977 because of the limited health, educational, and transportation resources. After the relocation, the island became a military base from 1977 to 2000. All the land was expropriated by the military.

The accessibility restrictions and the influence of the warm, plankton-bearing Kuroshio Current (pdf) has resulted in a surprisingly well-conserved area of rich natural and geological resources, home to many fish and coral reef species and a critical area for Taiwan’s offshore fishery. Over 50 hot spring vents lie in the sea floor near the “turtle head,” where a unique species of crab lives. There are around 16 species of cetaceans in the area according to studies. A diversity of more than 400 species of plants and 120 species of butterflies, snakes, birds are found in the island, as are two native Taiwan species, the endangered Formosan flying fox and the Formosan lily, as well as a native Chinese fan palm habitat.

Volcanic Turtle ( Guishan) Island – 17 minute video.

Limiting Carrying Capacity

Because of its amazing natural and marine resources, the government reopened Turtle Island for ecotourism in 2000 in response to demand from the tourism industry. To protect island ecology, capacity control was set at 250 persons per day, almost all brought in by ferry. Also, to ensure low impact on the environment, the supporting policy “Regulations for Guishan (Turtle) Island Ecological Tours” (Chinese only) was put into effect. The regulations prohibit fishing, hunting, feeding wild animals, taking any natural resources from the island, and importing animals and plants to the island.

In the first two years, the capacity limit caused some management problems. NEYC, a part of Tourism Bureau Taiwan, was struggling with pressures from local stakeholders, especially private accommodation businesses and ferry companies. Over 10,000 tourists applied to visit Turtle Island every day, but the low draw rate raised issues and complaints from both tourists and local businessmen on the main island.

Increasing Carrying Capacity

An endangered Formosa flying fox. Of the bat’s three Taiwanese habitats, Forest Bureau research shows that only the group in Turtle Island has grown steadily since 2010, suggesting that NEYC’s tourist carrying capacity plan has not harmed the ecosystem. Photo: Yang Yueh-Tzu

NEYC adopted a strategy of slowly increasing tourist capacity while keeping the ecosystem intact. The daily visitor capacity limit was gradually raised from 250 to 350 (2002), then 400 (2005), 500 (2007), 700 (2010), 1000 (2014), and 1800 (2015 to the present).

How did they do it?

It is easy for a DMO to declare it would like to set eco-social carrying capacity according to academic research, but when the DMO actually begins to implement it, stakeholder voices and facility capacity must be taken into account. There are always academic professors who strongly embrace ecological conservation without tourist access and who may not agree with rising visitation. Other professors will take stakeholder opinions and the environmental situation into account. The NEYC staff told me that there was no conflict in their discussion with professors.

In order to help the local economy by replacing the declining fishing industry with a growing tourism industry while still protecting marine resources, NEYC went on to hold meetings with local stakeholders at intervals on how to increase carrying capacity and improve the facilities so as to achieve a sustainable “ecological economy.” Following these discussions, including professors from marine, biological, and recreational departments, NYEC arrived at a plan that balanced the environmental research baseline with local economics. Considering that only a part of island (the tail part, around a tenth of its surface) was open to the public, the dock, hiking trails, and service facilities (toilets) could be improved and maintained.

Rebuilt stairways can handle increased foot traffic to the peak. Photo: Roi Ariel

The tourist-accessible area is around 19,835 square meters and the capacity baseline was originally set at 132 square meters per person in 2000. Visitation sessions were set at 150 people a session before 2010, then 250 people a session in 2010, under the operating procedure controlled by an NEYC guard team. Now tourists are usually split into four 90 to 120 minute sessions per day, with a limit of 450 visitors at the same time during March to November. (The island is closed during monsoon season from December to February.) Wednesdays are reserved for academic organizations only, up to 500 visitors, split into different sessions.

From the sign atop Turtle Island. Photo: Roi Ariel

Coastal guards monitor when tourists get on board and leave the island. Now, there are 13 recreational ferries with a capacity of 85-94 visitors, among which four ferries are owned by the former Turtle Island residents and the rest run by other locals in NEYC area. Most of the tour packages combine dolphin watching and hiking on the island, so some ferries can go dolphin watching first and take turns to get on the island.

Each group of visitors landed on the island has 90 to 100 minutes to tour along the trail system, guided by licensed guides. After a stop at the tourism center, tourists visit the temple and old primary school buildings, walk around the lake to explore biodiversity, and visit the military tunnel and abandoned fort where they can watch the sea.

According to the report, there are always requests for more facilities and carrying capacity. For example, overnight stay service and submarine tours were suggested. Because NEYC’s main target is to conserve the natural landscape and environment, development with big construction didn’t fit in their plan.

Control of Dolphin Watching

The dolphin/whale watching activity around Turtle Island began even before Turtle Island opened for tourists in 1997. As one observer has noted, “in 20 years, Taiwanese people changed to conserve the cetaceans instead of eating them.”

However, there were no regulations and no consideration of carrying capacity for tourists participating in a dolphin and whale watching package. Given that all ferries have must acquire a license from Yilan county to run a recreational business, the stakeholders decided to limit the number of licenses in the area to 13, tied to a code of conduct. That put an automatic limit on cetacean watching around the island.

The negative impact from dolphin watching activities brought together academics aligned with NGOs, the Fishery Agency, Council of Agriculture from the Taiwan central government to set up a voluntary certification system, “Whale Watching Mark,” in 2003. Among the 13 ferries, only 5 were certified. Due to the complicated documentation process required for certification, and given that green tourism was not mainstream enough in Taiwan, the Whale Watching Mark hasn’t received good responses from ferry companies until now. NEYC has also started to cooperate with Taiwan’s Ocean Affairs Council in monitoring dolphin research in the area. Since 2017, researchers have used GPS to track the sight-seeing ferries as an indicator of dolphin movements.

Sightseeing ferry at the edge of the Milk Sea. Photo: Monique Chen

As a DMO, the NEYC has tried to find friendly strategies to get more ferry owners to understand that chasing dolphins may harm the environment. By regulation, tour guides working for ferries and on Turtle Island must be licensed by NEYC twice a year. Through annual tour guide training, the ferry owners have gained more knowledge about protecting the marine dolphins. According to one captain, one protocol among ferries now is to take turns for 10 minutes for tourists to observe nearby dolphin families when more than one ferry approaches them.

COVID-19 and Beyond

During the Covid-19 pandemic, domestic tourism in Taiwan has soared as Taiwanese were not able to travel overseas. Some popular Taiwanese destinations encountered unprecedented negative impacts of overtourism for the first time. Even though tourist arrivals reached full capacity during weekdays, Turtle Island remained under control because of its carrying capacity system.

One challenge NEYC faces now is the “Milk Sea” close to the island, where “God has spilt the milk” as described by promotional agents. The Milk Sea refers to seawater with milky cream color caused by undersea hot springs. The tourism industry has touted this new sightseeing spot as a novelty, and tourists are flooding in. More and more yachts, stand-up paddleboards, and kayaks have come to this area, causing safety problems and conflicts with the ferry boats.

The Milk Sea from atop Turtle Island. Photo: Yang Yueh-Tzu

Fortunately, from 2016, NEYC has been implementing the GSTC Destination Criteria and participating in the Green Destinations Program has helped NEYC gain confidence and not only assess what they have done so far but also act on guidelines for achieving a more “sustainable-ecological economy” tourism pattern. Now some voices among original residents express hope that Turtle Island can be designated a cultural landscape heritage site and the history of their traditions and culture preserved.

Whatever changes to the Island may be, they will be based on official adherence to sustainability criteria. “‘Ecological Island’ is the main management strategy of Turtle Island, and the priority is to keep the eco-landscape and lower the construction impact in Turtle Island,” says Chia Feng Lin, Coordinator of NEYC.

Following the criteria, NEYC keeps on communicating sustainability principles and marine conservation to business owners, tour guides, and ferry owners, along with continued academic monitoring of Turtle Island’s ecological indicators .

To summarize, from the view point of sustainability, stakeholders’ voices and social conditions should be taken into consideration as well as academic research. Although the carrying capacity program may not be 100% perfect from scientists and researchers’ environmental protection perspective, NEYC has found a transforming strategy to meet the needs of the tourists, local ferry owners, and environmental conservation needs.

Hopefully, this example can inspire other destinations to find their own balance strategies.

Appendix

Monique Chen has supplied these additional links (some in Chinese only):

- Study on recreational carrying capacity in turtle island (2004; Chinese)

- Tour information for Turtle Island (English) – https://www.necoast-nsa.gov.tw/FileAtt.ashx?lang=1&id=1181

- Wild Animal Conservation Act in Taiwan from 2000 – https://law.moj.gov.tw/ENG/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?pcode=M0120001

- Visiting application web page of Turtle Island (Chinese only) – https://events.necoast-nsa.gov.tw/coast/

- Whale Watching Mark Taiwan – https://www.eastcoast-nsa.gov.tw/en/travel/whale-watching

- Blue Whale Ferry with Whale Watching Mark on website – https://www.h558882.tw/

About the Author

Monique Chen is the co-founder and chairwoman of Sustainable Travel Taiwan (STT) and a specialist as an urban planner and museum operator. She has been engaged in cultural and environmental preservation work for 20 years.